|

Reviews of Blue Hanuman:

"Larkin's first full-length collection since her Audre Lorde Award-winning My Body: New and Selected Poems radiates with control and brevity. Larkin's attractive, enigmatic poems hover near a precipice, electrically charged with nascent tension, a 'mute globe of held breath' delicately suspended. Divided into four sections, the poems are short, ekphrastic, or riddle-like explorations of the natural world. 'Legs Tipped with Small Claws,'

the title poem of her 2012 chapbook (Argos Books), describes a fishing spider: dangerous, sexy, and undoubtedly feminine. 'Sometimes it's her mate/ she liquefies to drink him inside out,/ then cleans each of her velvet legs.' Larkin doesn't rest at mere beauty, she digs deeper, probing at disturbances; the 'movement-in-stillness' of an old photograph, or the 'lush rage-orange' of a Francis Bacon painting. As for Hanuman, the collection's eponymous monkey god: 'his blueblack tail flicks upward,/

its dark tip a paintbrush loaded blue.' Themes of motherhood are threaded throughout, muddying the boundaries between animal and human concepts of nurture and climaxing in the book's final section of the book. Larkin's haunting lines encapsulate the feeling of reading this collection: 'You are inside me now, as inside you/ your mother: your shame-belly born from hers,/ my grief-lungs from yours, eyes of no mercy.'"

—Publishers Weekly

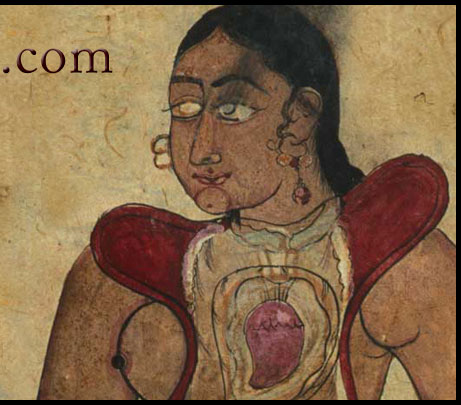

"Joan Larkin's new book takes its name from a painting 'bought for a few annas,' depicting the Hindu monkey god Hanuman ripping open his chest to reveal Rama and Sita, the perfect ruler and wife, hidden inside him. It is a fitting emblem for a book concerned with finding the human hidden in the animal, the spirit stuffed within the body, the past burrowed in the present and vice versa. Finding these hidden properties requires both delicacy and determination. They do not show themselves without pain. The poems—all short, most in one stanza—are like hard seeds that need to be cracked and ground. For example, in 'eye,' a strange underwater arctic beast some of whose legs 'eat what blooms/ between ice crystals' speaks to us only after we have sent our camera down 'six hundred feet/ under the ice shelf.' Sometimes we get there almost too late, as in 'The Porch' in which Larkin observes a spider producing a 'shining dome' out of her 'small steel body' to preserve the corpse of a moth caught in her web.

All animals live on other life. Their survival requires the death of other living beings. The ravages of life are ravishing in these poems. 'Weddell Seal,' one of the simplest and most extraordinary poems in this marvelous collection, issues from the voice of the seal who 'fell from sealmother's/ liquid womb into fast-ice/ and she suckled me with her thick/ milk and kept me, fifty days.' It ends fifteen lines later with the seal old and toothless, the prey of other predators, aware that 'sea-stars, worms, and flesh-eating/ amphipods will slowly cover/ me and devour my meat.' Until then, she remains 'standing in the wind,/ seal flesh still warm.' Now in her seventies, Joan Larkin is a poet used to standing in the wind, but her flesh glows with primordial heat."

—David Bergman, The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide

Reviews of My Body:

“For nearly 40 years, Joan Larkin has written poems that stake out a territory of relentless self-examination, taking on love and death, family and sexuality in a voice that is unsentimental, ruthless and clear-eyed. Born in 1939, she is of a generation of women who often subjugated their truer selves to social expectation; that tension, which culminated in her coming out as a lesbian, is fundamental to her work.

Larkin is also a recovering alcoholic, and her poems about this experience are among the finest ever written on the subject — the testimony, without cant or doctrine, of someone who has survived. For her, poetry is a form of witness; she offers no false hopes, no resolutions, except to reflect, as honestly and directly as she can manage, the complicated, at times uncontrollable, messiness of being alive.

My Body: New and Selected Poems gathers generous samplings from Larkin's three previous collections, as well as a substantial array of new material. It's a remarkable statement, tracing the evolution of a poet from her earliest efforts ("My mother gave me a bitter tongue. / My father gave me a turned back," she begins "Rhyme of My Inheritance") to the stunning sweep and simplicity of her current work.

I'm older than my father when he turned / bright gold and left his body with its used-up liver / in the Faulkner Hospital, Jamaica Plain," Larkin writes in "Afterlife."

Best of all is the transcendent "Blackout Sonnets," a sonnet crown (seven linked sonnets, joined by repeating first and last lines), which originally appeared in her 1986 book, "A Long Sound.” "I drank anything and slept with everyone," she acknowledges, "and kept my mouth shut about the abortion."

This is poetry without pity, in which despair leads not to degradation but to a kind of grace.”

—David Ulin, Los Angeles Times

"There are few poets in America who can combine Joan Larkin’s formal mastery with her emotional intensity, and so it has been something of a mystery to me why she’s not better known or more widely valued as one of the finest poets in America. Unlike so many poets who lose emotional force as they get older, Larkin grows stronger as time goes on. The new poems in this volume are by far the best she has written. Perhaps Larkin’s failure to win a wider audience is the result of her tackling for many years a subject that men would like to claim as their own—alcoholism. If you put Franz Wright’s poems of drunkenness beside Larkin’s, it’s perfectly obvious who has written the better work. Yet Wright gets published by Farrar Straus and Larkin by Hanging Loose Press. But I think Larkin’s limited recognition also derives from something else: Larkin gives no place for the reader to hide, no easy consolations to cheer you up no matter how bleak things are. And things are bleak—but also joyous and mysterious—and you’d better get used to it and pay attention so that you can see that “Heaven is fire, too.” Unlike so may AA veterans, Larkin retains no belief in a higher power. As she writes in “Tough-Love Muse,” “Praise grief all you want,/More loss is coming.” But Larkin deserves no more loss. The arrival of the recognition she deserves should be on the way."

—David Bergman, The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide

“In a youth-addicted culture, it is a pleasure to read the work of grown women. Having recently arrived (full disclosure) at threescore years and ten, I find myself less often surging to read prizewinning first novels and books of poems by brilliant young authors, and more inclined to see what maturity has to say. Women’s wisdom, as well as artistic finesse, is what I seek nowadays in poetry. In particular, poets who prove themselves able to face the worst, in the body politic and the body, and to survive unsubdued, win my gratitude. Here are two such poets. . . .

Reading the new poems in Joan Larkin’s My Body, you will find yourself thinking you’d like this poet as a friend. Scene after scene, whether she is writing of her daughter’s birth, or a man’s ecstatic testimony at an AA meeting, or the AIDS deaths of friends, or poignant memories of parents, or aging kin, or “faking boredom” as a high school girl starting to be a serious drinker and watching “as Ella in a black gown landed exactly/ on each note of From This Moment On,” or being beaten by her mother, or abortion, or hot sex, or cold sex, or demonstrating at a presidential inauguration while the black Stetsons and draped minks sneer by, “faces smooth and satisfied/ The bullies’ feast was beginning”—every poem is a document of awesomely generous attention and care. Here in its entirety is a poem entitled “The Atheists,” near the end of a gritty sequence about the poet’s brother and his dying wife. Eight lines seem to suggest the whole story of four characters:

I surprised myself calling the priest Father.

He was 5’5”, thin hair combed slant.

He leaned on the syllable us in Jesus

and smiled and nodded through the tapes I played,

Ave Verum corpus and the dead woman singing a lullaby.

And Donald took the brass cross that had touched her coffin

and hung it over his bed for comfort,

choking tears of shame as he told me.

Larkin has not only the clear-sighted compassion of a Chekhov, but also his instinct for narrative and some of his sly wit, especially when targeting self-importance. I remember my glee reading, back in 1975, “Vagina” sonnet, from her first book, Housework.

Here’s the octet:

Is “vagina” suitable for use

In a sonnet? I don’t suppose so.

A famous poet told me, “Vagina’s ugly.”

Meaning, of course, the sound of it. In poems.

Meanwhile, he inserts his penis frequently

into his verse, calling it, seriously, “My

Penis.” It is short, I know, and dignified.

I mean, of course, the sound of it. In poems.

Then came the snappy close, in which the poet decided it was

a waste of brains—to be concerned about

this minor issue of my cunt’s good name.

I enjoy seeing naughtiness done in strict iambic pentameter, and it’s because Larkin (like Rich) was so well trained in traditional prosody that she (like Rich) also handles looser forms so well. Is it because she was so well trained in trouble—abortion, early marriage and divorce, alcoholism—that she handles human pain so well? Larkin’s list-poem “Inventory,” 41 lines long, may be the best single poem I have ever read about AIDS. It includes lines like these:

One who lifted his arm with joy, first time across the finish line

at the New York marathon, six months later a skeleton

falling from threshold to threshold, shit streaming from

his diaper....

one who refused to see his mother,

one who refused to speak to his brother,

one who refused to let a priest enter his room,

and its final line is “one who wanted to live till his birthday, and did.” Numerous elegiac poems to friends and kin create their personalities so clearly and kindly that you think you know them yourself. Also numerous are poems evoking love affairs long and short, “the hot feast” on one occasion and “she smeared the lube/ the way you’d spread margarine” on another, equally precise. An early crown of sonnets on what may or may not have been a rape had me holding my breath, and at the same time burning with admiration for the poet’s acknowledgment of complicity. When Larkin in the title poem of My Body gives us a lengthy list of its flaws, but concludes that it is “still responsive to the slightest touch,/ grief and desire still with me,” and “healed and healed again,” I can only applaud.”

––Alicia Ostriker, The Women’s Review of Books

Joan Larkin and the Poetics of Lesbian Inclusion

History indicates that at a crucial moment in post-sixties politics a rift formed between lesbians and gay men. As Dudley Clendinen and New York Times reporter Adam Nagourney write in their monumental Out for Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America, the nascent queer movement of the early seventies was rife with conflict between lesbians and gay men, a tension that began—how else?—with a party. It appears that the New York version of the radical queer organization, the Gay Liberation Front, sponsored community dances in Greenwich Village, and the men wanted to arrange things to their liking (read: overcrowded dance floor, hyperactive strobe lights, deafening music with sometimes sexist lyrics, non-stop grope fest)—a situation that the lesbian members, who wanted a place to meet and talk to other lesbians, found deplorable. “Women were lost to each other in a sea of spaced-out men,” activist Ellen Shumsky said, and I wonder to what degree, in the first decade of the 21st century, are lesbians and gay men still living separate lives?

Though no easy answer readily presents itself, hints may be found in both the culture at large and, in particular, contemporary poetry written by lesbians and gays, including the poems found in Joan Larkin’s My Body: New and Selected Poems. In the December 24-30, 2008 issue of The Village Voice, for example, I read that “Sandra Bernhard has accomplished the difficult feat of being both a lesbian and an icon among gay men,” a statement which takes for granted gay male exclusion of lesbians. I find that a bar called Saints advertises itself as “one of the only mixed gay / lesbian bars in Manhattan,” implying a high degree of social separation between the sexes. Then there’s Milk, directed by out filmmaker, Gus Van Sant, which, despite its nearly complete omission of lesbians such as Sally Gearhart, and its minimization of the essential role women played in Milk’s successes, has garnered rave reviews and won two Oscars, including Best Actor. I fear that poetry might not offer better results, a hunch made real by a panel presentation at the 2008 Associated Writing Programs Conference in New York City.

Following introductory words by the late and greatly missed Reginald Shepherd, the panel entitled “Gay Male Poetry Post Identity Politics” began with Aaron Smith (followed soon after by Christopher Hennessy and Brian Teare). After presenting a photograph of actor Daniel Craig, rising in his Speedo from ocean spume and complete with gigantic hand-drawn genitalia, then reading a poem by Joe Brainard called “Sex,” Smith told the nearly all-male crowd an anecdote about a friend who “wants his new book to be about something other than cock because that’s all gay men write about.” Smith, who found “an undercurrent of conservativism [sic] in his statement” responded by asking, “Can you please tell me which poets are currently writing about cock, because those are the poets I want to read?” Since nearly every gay male anthology after 1973 includes an array, if not a veritable smorgasbord, of sexually explicit poems, and since one can name dozens of gay poets who write graphically about sexuality, including myself in my first book, I was shocked by Smith’s comments. But what shocked me more was the visible tension that arose between gays and lesbians at the end of this panel.

The speakers, who had collectively mentioned three lesbians (Hennessy quoted Joan Larkin and referenced Elena Georgiou, and Teare gave an anecdote about Elizabeth Bishop), had gone overtime. The panelists and audience, nearly all of whom were women, had arrived for the next talk, “We Will Be Citizens: The Insistent Voice of Lesbian Nonfiction.” The women appeared eager to begin. But the previous panelists, who talked to individuals from the audience for some time, seemed to be unaware of them. By the time the men left the room, the women were scowling. But the departing didn’t seem to notice; they were joking, smiling, hugging. The separation between lesbians and gay men couldn’t have been more apparent.

Afterwards, walking through Midtown, I asked myself to what degree queer poets—both female and male—traffic in tactics of exclusion in our work? Is there, as many lesbians avow, a disparity between the inclusion of gay men in lesbian poetry and a lack of images of lesbians in gay male poetry? What can the state of our poetry tell us about gays and lesbians in relation to each other? Are these two groups as separate as a cursory view of the landscape implies?

***

For the sake of full disclosure I should say that I, a gay man who began his writing life beneath the shadow of the AIDS scourge, have always read poetry by out lesbians. As was the case in the mid-eighties when I bought my first book of poems not required for a college course (Adrienne Rich’s Poems: Selected and New, 1950-1974), when I read poetry of achievement by lesbians I feel a cooperative system at work that is daring, alluring, sacrilegious, sacred, compelling, anti-authoritarian, and downright humane in its penchant for inclusiveness. One needs no better example than Joan Larkin’s My Body: New and Selected Poems to demonstrate this sense of inclusion.

Larkin’s aesthetic is dedicated to an extraordinary scope of vision. In her rage against injustices, in her compassion, in her celebration of the human spirit to survive despite the odds, Larkin explores subjects as diverse as illness and death of family members, alcoholism, child abuse, abortion, the joys and difficulties of lesbian union, and—my emphasis here—the lives of gay men.

Larkin’s work spans the years between the Gay Liberation Front’s internal struggles and today’s post-Prop-8 world. In addition to being a chronicler of her age in four acclaimed books of poems, one book of translations (with Jaime Manrique), and six plays, Larkin has been a pivotal figure in publishing poetry by out LGBT writers. At a crucial moment when few general circulation publications would print out queer poems, Larkin co-edited (with Carl Morse) the groundbreaking anthology Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time (1988), which won her her first Lambda Literary Award. More recently she was the first poetry editor of Bloom, one of the few U.S. periodicals that publishes work by both lesbians and gay men.

Within a few pages of the opening section of new poems in My Body, it’s clear that in Larkin one finds an array of human beings doing their best (and sometimes worst) to live and die. Among the people found are a newborn handed to its mother in the hospital, a father dying of melanoma, a mother who screams “I hate my life” as she scrubs a kitchen floor, a “nice Boston girl” the speaker takes to Brighton, 92-year-old Aunt Flo, one “Harvey Smith, odd duck of Cambridge, Mass.,” a lover named Dot, a brother named Don, Joan of Arc, Biblical Mary who tells the Jesus birth story from her point of view, and no-holds-barred explorations of alcoholism, an addiction occurring at a higher rate among lesbians and gays than in the general population.

As The Los Angeles Times recently observed, Larkin’s poems about alcoholism “are the finest ever written on the subject,” an opinion with which I agree (with the caveat that Maggie Anderson’s “The House of Drink,” first published by Larkin in Bloom, is a close rival). One aspect of Larkin’s poems on alcoholism is that they refuse to allow the reader to be a mere observer. Here are the opening lines of “Testimony”:

I wasn’t the only drunk reaching

for Kleenex as short Arnold

on the foot-high platform

choked the wild sound

rising in his throat.

The reader discovers that there are “two hundred of us” in what appears to be an AA meeting, and that everyone is silent, in awe of Arnold’s anguish. A moment that in lesser hands could easily have yielded sentimentality rises, in Larkin’s artistry, to include us all. Whether she or he has ever attended AA or not, the reader becomes, in a few lines, a participant in the life struggles of every women and man in that room: Mary, Sybil, John, Steve, the unnamed many. The end result is to pull the reader into the most human, fragile, and, simultaneously, the most tensile strength imaginable: being vulnerable in the presence of others. The poem’s final line—“I wish you’d been there”— reminds the reader that she or he was (and always is) there, among the human subjects, with their disasters and fears, their pride and crushing defeats, and that most precious human attribute, the will to persevere.

Though “Testimony” does not indicate who is gay or straight, in other poems, Larkin renders male homosexuality directly. In “Denis,” we find a figure who “offered yourself at the rest stop” and “came back as God’s roar in a dream.” But it is perhaps Larkin’s highly accomplished AIDS poems that best demonstrate her power to empathize with gay men. “Waste Not,” “Photo” (with its reference to artist Peter Hujar), “In Time of Plague,” “Sonnet Positive,” “A Review,” “The Fake” are all hard-hitting and sorrowful poems. And “Inventory,” a poem which critic and poet Alicia Ostriker indicates “may be the best single poem I have ever read about AIDS,” is the most emotionally engaging of them all:

one who went to Mexico for Laetrile,

one who went to California for Compound Q,

one who went to Germany for extract of Venus’ flytrap,

one who went to France for humane treatment,

one who changed, holding hands in a circle,

one who ate vegetables, who looked in a mirror and said I forgive you. . . .

Perhaps taking its form from Anne Sexton’s “In Celebration of My Uterus,” “Inventory” renders the entire AIDS struggle—its humiliations and violence, its worldwide scope, its desperation—in a mere 40 lines.

Though one may attempt to argue that lesbians include gay men in their poetry because of the extremity of HIV / AIDS, it should be noted that from the beginning gay male presence appears in Larkin’s work. “Direct Address,” a poem from Housework, was published in 1975, only a few years after the tension at the Gay Liberation Front’s dances. In the poem, the female speaker warns her male interlocutor who wants to “be a woman” that not only is his notion of womanhood sentimentalized, but that “the heart is sexless.” “I think it only fair to warn you,” Larkin’s narrator continues, “it is not what you think / trailing your skirts, / brow-pencil, night cream— / these aren’t the feminine / or any softnesses you were denied / but some extreme costume of the heart.” What I am reminded of is how some gay men who appropriate feminine values—an honorable proposition in itself—may not fully recognize the difficulties of womanhood. Is perhaps some of the reason for the tension between lesbians and gays a sense on the part of lesbians that gay men sometimes wish to appropriate female qualities without having investigated, in any comprehensive way, what women’s lives are really like? If we move past the ironies of camp, past the vagaries of stereotyping, past fantasy, what we end up with is the fact that women, who are at this moment making 79 cents to every male dollar, still have to fight like hell to get out of the hegemonic kitchen! What the man who wants to be female might get—cross-dressing or post-op—is a dunk in the cold tub of exclusion, of attempted erasure, as if in the eyes of the world, (s)he is, de facto, a second-class citizen.

Like Larkin, many other self-identified lesbian women poets write about gay men. It is not difficult to discover memorable poems written by lesbians (and, it should be noted, heterosexual women as well) that address HIV / AIDS. Marilyn Hacker, Olga Broumas, Maureen Seaton, Michelle Cliff, Eileen Myles and many others have published their poems side-by-side with gay men in anthologies such as Poets for Life: Seventy-Six Poets Respond to AIDS (1989) and Things Shaped in Passing: More 'Poets for Life' Writing from the AIDS Pandemic (1997). In individual volumes written by women, one easily finds poems that address issues of import to gay men. I opened Eloise Klein Healy’s Passing and found “Site for Young Man Dying,” with its “strobe-ball / in a boy-dance bar” and “Who knew the ways / AIDS would change everything.” Beatrix Gates’ “Deadly Weapon,” from In the Open, is dedicated to “[the] memory of Charlie Howard, gay man murdered in Bangor, 1984.” And from the aforementioned Poems: Selected and New by Adrienne Rich, one notes “For L.G.: Unseen for Twenty Years” which addresses “the strange coexistence of two of any gender.” In a matter of minutes I found lesbian poems with gay male subjects.

But when I turned to poetry written by gay men, the task of discovering representations of the opposite gender became an uphill battle. Though I quickly recalled Frank Bidart’s brilliant dramatic monologue, “Ellen West,” with its focus on a woman whose “homo-erotic component [is] strikingly evident,” try as I might I couldn’t find any Ginsberg poem that takes on lesbian lives as its central subject matter. I found zilch in Auden, Merrill, and Hart Crane. Though of course it wasn’t possible to read every word of these prolific poets, at least one of whom I consider a beacon for my own work, I don’t think there’s much room to argue that their remarkable output contains many poems of gay / lesbian camaraderie. After considerable effort I finally found “Aunt Toni’s Heart” by Rafael Campo (Aunt Toni being a motorcycle-riding lesbian who “brought Charlene with her, blond hair / Drawn back beneath their helmets”), Alfred Corn’s “Letter to Marilyn Hacker,” and Richard Howard’s “A Sibyl of 1979,” concerning the inimitable Muriel Rukeyser. However accomplished these poems are, it may be noted that they belong to a very exclusive club we might christen Dare Speak the Name Lesbian.

Had I missed something? Had I never bothered to notice how few gay male poets write about lesbians (or, for that matter, much about women in general)? While of course recognizing the courage required to come out in print, have gay male poets been so concerned with celebrating sex and desire that we have fetishized sexuality to the degree of excluding a whole host of possible subjects? In order to further respond to these questions, I took from my library the first queer anthology I saw, The World In Us: Lesbian and Gay Poetry of the Next Wave.

Edited by Elena Georgiou and Michael Lassell, and published in 2000, The World In Us includes an equal number of female and male poets (twenty-three of each), some of whom are among the best poets writing today. But what I discovered is that of the 103 poems by men there are a paltry five references to lesbians. The first appears on page five in Mark Bibbins’ “Mud”; but you have to wait 181 pages to find the second, in Timothy Liu’s “Strange Fruit,” a poem concerning a hate crime perpetrated against a lesbian couple. Of the three other poems which include lesbians, only one, David Trinidad’s “Moonstones”—dedicated to Joan Larkin—focuses on lesbian lives. More often than not, women are presented as family figures (with “mother” garnering twenty-two citations, “grandmother” four, and “aunt” two), or as camp / cult icons, Jackie Onassis, Marlo Thomas, Ann Landers, Connie Stevens, Susan Hayward among them. The names of these camp / cult figures appear ten times, twice the number of times one finds lesbians in these pages. Perhaps the most disturbing observation is that this trend extends across all demographics—race, age, state of residence—indicating how entrenched and pervasive is the exclusion of lesbians in the poetry by gay men.

Conversely, when perusing the 100 poems by lesbian-identified writers included in The World in Us, I quickly discovered a wide variety of poems that include gay men. Gerry Gomez Pearlberg’s “Loop-the-Loop in Prospect Park (1905),” a poem inspired by a photograph from George Chauncey’s Gay New York and concerning a cross-dressing hustler; Linda Smukler’s series of poems which blur genders and explore the violence of sex and fantasy; Leeta Neely’s “Multiple Assaults,” a poem grounded in drug abuse, HIV, and hate crimes; the gender-bending of Minnie Bruce Pratt’s “The Other Side”; Robyn Selman’s “Exodus,” part of which addresses the female speaker’s male date and their realization that they are both queer; and of course poems about HIV / AIDS, from Honor Moore’s “Edward” to Joan Larkin’s “Inventory”—all appear in this anthology. In fact, the majority of the lesbian poets in The World in Us include gay men within the parameter of their writing lives, something that cannot, it seems, be said of the male poets included here.

* * *

Joan Larkin, like every lesbian I approached concerning this subject, is aware of the problem. In a 2005 letter to the editor of the Gay and Lesbian Review, Larkin confronted the magazine about its “Poetry Issue:

“Maybe it’s time you renamed the magazine The Gay Male Review or perhaps The Gay & Token Lesbian Review. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised—I’ve long been chagrined at how underrepresented women are in your pages––but I was stunned and insulted by the lack of any real discussion of poetry by gay women in something calling itself ‘The Poetry Issue.’ One piece on one lesbian poet out of seven articles. . . is even less inclusive than the abysmal record of The New York Times Book Review.”

The understandably angry tone of Larkin’s letter, as well as its content, sounds similar to what women were saying about gay men excluding them in the seventies. “Most gay men don’t understand lesbian women any better than most husbands really understand their wives,” averred Rita Mae Brown in those early days of queer liberation. One may even go so far as to wonder if straight men, with their taste for lesbian pornography, are not ahead of queer men on this score. After all, lesbian porn at least requires really looking steadily at the subject at hand.

Forty years after Stonewall, a change of world is still in order. To recognize our shortcomings is the first step toward overcoming repetitive behavior. Any artist worth her salt will tell you that repetition, in our writing, equals death. If gay men are not including many women in our poems, who and what else are we excluding? If maintenance of the status quo is the quintessential conservative gesture, is it not in our best interests as gay poets to take the progressive road less traveled and expand our subject matter? To write about new subjects while maintaining our erotic eye on the milk and honey down below and our obsession with glamorous stars is one way toward progressive aesthetic values. Subjects not commonly found in gay male poetry include men raising children, the confrontation of homophobic politicians, love of wilderness living, explorations of interplanetary space, growing older (J.D. McClatchy’s “My Mammogram” is a superb example), and of course camaraderie with women and explorations of the female body (and, it should be noted, gay physicians such as Rafael Campo and Peter Pereira write far more poems about female experience, but does it really take the placement of M.D. after our names to regard the ordinary miracle of women?). As much as I would like to say that gay men have fully embraced, befriended, stood by, lived with, and, yes, loved our lesbian sisters, gay poetry demonstrates otherwise. The least we can do is to allow lesbians to live in our imaginative work, especially considering the seriousness with which lesbians have written about us.

––Richard Tayson, Pleiades 29.2

|